WHERE do fountain pens belong in today’s world? In the corners of department stores, dusted off only when buying a fancy gift? Or perhaps in the jacket pocket of a high-flying executive, until an expensive toy is needed to be shown off?

From The Fountain Pen Community

It wasn’t an incomprehensible time ago that fountain pens were ubiquitous. The late 19th century saw the start of the mass-produced fountain pen. Unlike its predecessors, it successfully mated the ink supply with the writing implement proper. It was a self-contained gestalt tool—the founding of the modern pen as we know it. By the early 20th century, it was indispensable in the workplace and the home.

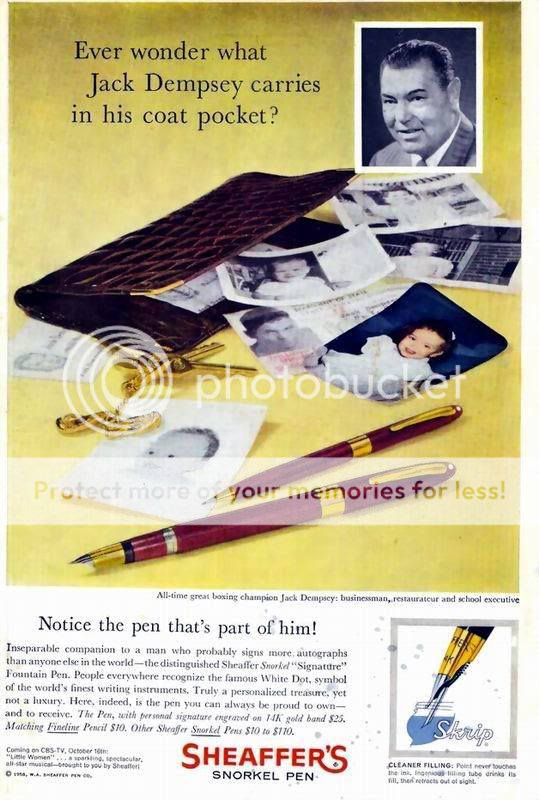

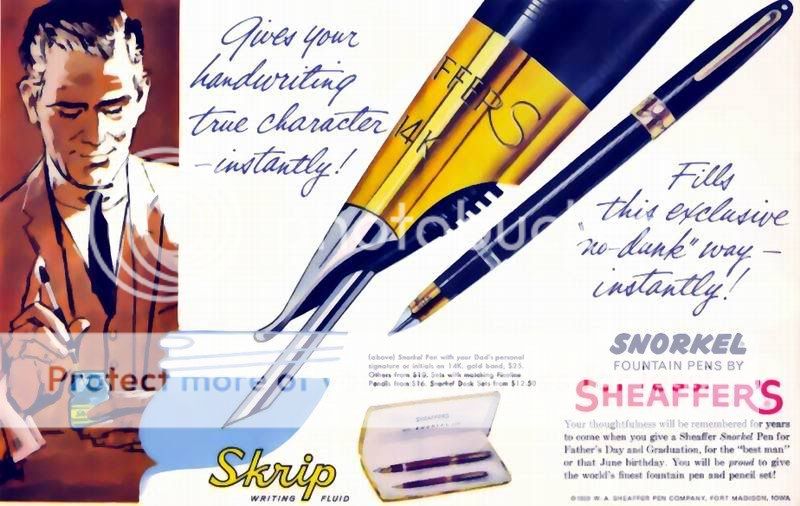

The Sheaffer Snorkel: possibly the most complex fountain pen ever made. From The Fountain Pen Community.

The fountain pen’s base design principles have changed little. A reservoir of ink lead to the feed, on top of which sat the nib. Everything would be wrapped up in an ergonomic body of some sort—the earliest fountain pens were made of ebonite, a type of hard rubber, before plastics came to be.

It is the simple-yet-complex relationship of these three parts that gives the fountain pen its magic. The ink reservoir is be refillable; initially it was disassembled and ink dropped in with a pipette, but these quickly gave way to creative and sometimes amusingly complicated self-filling systems. The feed is perhaps the most complex part of a fountain pen, an arrangement of channels and fins that allow ink into the nib and air into the reservoir—this air-exchange mechanism is essential, and an incomplete understanding of the physics involved was one of the reasons the fountain pen was not developed earlier. The nib was historically cut from alloys of gold, necessary to resist corrosion from ink. The tip, the part that would touch the paper, was made from iridium—an ultra-hard metal that would not wear down. The slit would conduct the ink to the paper through capillary action—the ink is literally sucked into the paper upon the lightest of contact.

Being the part of the pen that touches the paper, it is the nib that is the defining characteristic of a fountain pen. The ideal nib glides smoothly across the paper while giving just a hint of feedback, and leaves a rich, wet line. The qualities of this line are endlessly variable, depending on the qualities of the nib. The tip can be ground to make a line as thin or thick as you like, or even one that varies. Italic- and stub-shaped nibs are popular with those looking to showcase their calligraphy, or simply to add flair to everyday handwriting. The tines can be as stiff as a nail, giving a constant line, or they can flex with pressure, allowing artful control of line width. A fountain pen user could potentially customise a pen to fit their exact needs. Some maintain that constant use over the years even morphs a nib to fit your own peculiar style.

It’s these sorts of traits that separate the fountain pen from its more contemporary successors—namely, the now-pervasive ballpoint pen. It was some time in the 1960s that ballpoint pens became practical and cheap enough to ensure their dominance. The fundamental difference between the two is that the former was made to be lasting; the ballpoint pen was not.

Yes, ballpoints can be refilled, but it’s just not the same when you’re discarding the entire mechanism each time—the equivalents of the reservoir, the feed and the nib all go in the bin. A fountain pen can be reused with zero waste—save for the ink bottle. A good pen might even last a lifetime.

Of course, there’s a reason fountain pens fell from favour. Practical reasons for using them over ballpoints are very few indeed. One such reason is that the lighter pressure and lower angle required from their use can benefit those with hand problems such as arthritis. Some think that using a fountain pen trains you out of bad writing habits. Beyond that…well, they’re more expensive, they’re easier to damage, the ink tends to be less permanent and more prone to feathering and bleeding, a poorly-set-up nib can render the writing experience horrendous, and there’s the ever-present fear of leaking (though for a quality pen, this is a rare occurrence).

In return, however, you get personality and character. Unlike a ballpoint or rollerball, a fountain pen requires a definite level of operation, of hands-on involvement. The interplay of the ink and the pen and the paper can be a quirky and sensitive relationship. Getting the combination of all three just right is a process that can be aggravating, but also appeal to the tinkerer. And then there are the ink colours, far more than just blue and black—or even red and green and purple. Ink specialists Diamine alone have over a hundred shades in their catalogue.

So, where does a fountain pen belong today? As with many anachronistic diversions, fountain pens today have a small but enthusiastic following—and not just collectors of antiques, but everyday users. There is an active second-hand market for vintage pens, the tough and workmanlike things they were created to be. As for manufacturers, many of the old names are gone, but fountain pens never stopped being produced.

Some of the great American companies that spearheaded the fountain pen revolution—Waterman, Parker and Sheaffer—are still around, though their offerings are a little tepid compared to their heyday; a time when they were trying to outdo each other with the most outlandish filling system. Montblanc, famous for their Meisterstück pens that were first released in 1924, are a well-known luxury brand. Pelikan, makers of one of the first piston-fillers in 1929, are known for their exquisite piston-fillers today.

Newer designs have also made an impact. Two of Lamy’s most well-known pens are the Lamy 2000 (released in 1966) and the Safari (released in 1980). Newer manufacturers such as TWSBI and Edison Pen Co were formed within the last decade. Nostalgia may not the only reason to get into fountain pens. In fact, over in recent times, sales of fountain pens have been increasing.

A modern fountain pen isn’t drastically different. Improvements in corrosion resistance means that steel nibs are now widespread. Cartridge/converter fillings systems are by far the most common—these accept either disposable pre-filled cartridges (which are largely shunned by enthusiasts) or a small detachable piston reservoir called a converter. Higher-end pens are more likely to have a gold nib and a more traditional pistol-filled setup.

They come in their own numerous options. If transparent blue is your thing, there’s a pen out there for you, as there is if you’re looking for vintage tortoiseshell with art deco inlays. They can be as cheap as a pound apiece, or you can spend hundreds on a handcrafted one-of-a-kind lacquer pen from Japan.

The fountain pen holds an attraction to someone looking for something a little less forgettable. There’s an elegance to be found in craftsmanship made to last. They’re a little old-fashioned, perhaps, but some things never go out of style.

Until next time,